Energy

Digital comics

Naturam Superat

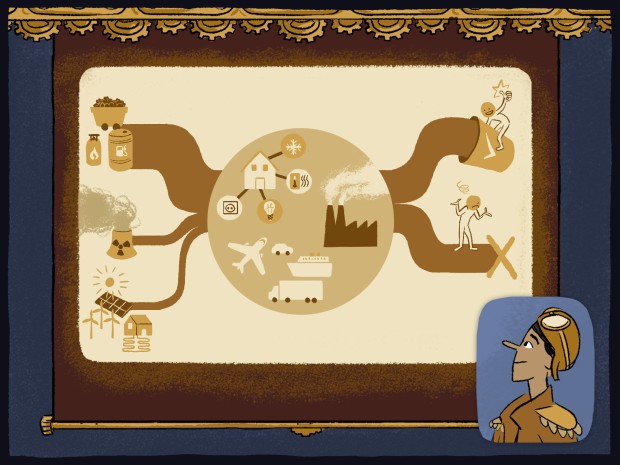

The Supertroupers want to devise a stage device with energy superpowers but are defeated by the physics of energy. The head technician encourages them to challenge their assumptions and stage the great energy challenges of our time.

Share this link ith your students

-

Overview

In this episode, the characters explore the concept of energy while preparing a theater play about the design of an energy superpower machine. As they discuss different aspects of the play, they encounter real-world questions about energy transformations, conservation, and dissipation. Their dialogue leads them to question whether energy can be "used up" and how we can distinguish between useful and non-useful energy. By engaging with historical experiments and conceptual discussions, they progressively refine their understanding of energy as a unifying principle across different domains of physics, chemistry, and biology.

This episode, along with its accompanying teaching materials, aims to help students develop a qualitative understanding of energy conservation and dissipation. Through guided discussions, historical perspectives, and hands-on activities, students will recognize that energy is always conserved but can become less useful depending on the system and its intended purpose.

-

Students point of view

The concept of energy presents well-documented challenges in secondary science education. Several factors contribute to these difficulties:

The abstract nature of energy – Energy is not directly observable, making it challenging for students to conceptualize.

The polysemy of "energy" – The term is used in everyday language in multiple ways, leading to confusion between its scientific and colloquial meanings.

Disciplinary perspectives – Energy is introduced in different subjects (physics, biology, geography, etc.), often with varying definitions and applications.

System identification difficulties – Students struggle to differentiate between a system and its surroundings, complicating energy analysis.

These difficulties contribute to common misconceptions, including:

Misidentification of energy – Students frequently confuse energy with force, power, or temperature.

Misinterpretation of energy conservation – Many believe that energy is "used up" or "lost," rather than transformed.

Alternative conceptions of energy (Watts, 1983; Trumper, 1993):

Anthropological view – Energy is associated only with living beings.

Substantialist view – Energy is treated as a tangible substance that depletes like a fuel.

The aim of this episode is to address these misconceptions by emphasizing energy conservation and energy transfer along an energetic chain, while highlighting the distinction between energy associated with physical changes being "useful" or "non-useful" depending on the observer's perspective.

-

Conceptual approach

The episode introduces different key ideas that can be named as energy-related-concepts.

1. To think in terms of energy, it is essential to first define the concepts of physical state and change. The physical state of an object or system consists of measurable variables such as position, velocity or temperature at a given moment. A change occurs when at least one of these variables varies between an initial and a final state.

2. A qualitative approach to energy helps to establish an intuitive understanding: Different initial states can sometimes lead to the same change, meaning they have an equivalent capacity to produce that transformation. For example, a glass of water can be heated to the same temperature through many different mechanisms (by friction, by compression, by sun radiation, by heating in an oven, etc.). This equivalence allows scientists to introduce the concept of energy as a measure of the capacity to produce changes. With this framework, energy becomes a tool to compare different transformations and understand their relationships.

3. Energy transfer can also be understood as a chain of changes. In everyday life, changes rarely happen in isolation; rather, one transformation triggers another (this can be metaphorised with the Goldberg Machines). Although energy is not a physical substance moving from place to place, the language of "energy transfer" helps describe these processes in a simplified manner. This conceptual tool allows for discussions about energy storage and energy transfer making it easier to track transformations in complex systems.

4. The rate of energy transfer also plays a crucial role in how changes occur. The same transformation can happen at different speeds depending on the power of the energy source. For instance, melting a chocolate bar under a weak light bulb takes much longer than using a more powerful one. This illustrates the importance of power—the rate at which energy is transferred—when analyzing energy chains and efficiency.

5. When considering energy transformations, it is useful to differentiate between useful and non-useful changes depending on the context. In a bulb, the visible light is a useful change, while the heating of the bulb is not. Similarly, in a toaster, the desired change is the increase in temperature of the bread, whereas the emitted red light is an unintended consequence. Physicists refer to the phenomenon of diminishing useful energy along an energy chain as energy degradation.

6. Energy degradation is a natural consequence of all transformations in nature. Every time energy is used to produce a change, the system's ability to generate further useful transformations is diminished. This means that the amount of energy available to perform intended changes decreases over time, as it disperses into less useful forms.

7. If energy is degraded, why do some changes around us keep going indefinitely? In those cases, additional energy from external sources must be introduced into the system to compensate for these losses. This occurs, for example, in many biogeochemical cycles, such as carbon cycle or water cycle, since Earth’s energy system is sustained by continuous energy input from the Sun. Without this external source, the ability to sustain large-scale changes would decline.

8. Despite energy degradation, the total amount of energy remains conserved. If one were to measure all energy transfers, including useful and non-useful ones, the total value would remain constant. A historical approach is used to illustrate this concept, focusing on Joule’s paddle-wheel experiment, which demonstrated that heat is not a substance but a form of motion. This experiment played a crucial role in developing the concept of energy conservation, even though Joule himself did not frame it in those terms.However, in practical applications, reducing energy losses through efficient processes can help maximize useful transformations. By increasing efficiency, we can control the fraction of energy that remains available for desired changes.

9. At this point, an important question arises: If the total amount of energy remains conserved but across an energetic chain the total amount of useful energy decreases in each step, where does the “rest” of energy go? As energy degrades along a chain, it typically disperses into the environment as heat, sound, or microscopic motions of particles. While this dispersed energy is still present in the system, it becomes increasingly difficult to harness for further useful work. Understanding this concept helps students grasp why continuous energy input is necessary for sustaining complex processes in both natural and technological systems.

10. In order to represent the quantity of energy transferred in an energy chain, Sankey diagrams can be used. This is a type of flow diagram in which the width of the arrows is proportional to the flow represented. Sankey diagrams can be used to visualise, on the one hand, the energy input required to operate one or more systems (lamps, vehicles, heating, etc.). In other words, the distribution of the energy produced by the system(s) from the incoming energy (in particular, what is actually ‘useful’ for the operation of the system, and what results from a degradation of the incoming energy, referred to as ‘useless energy’). The Sankey diagram has the advantage of showing the quantities of incoming and outgoing energy and, in accordance with the principle of conservation, the sum of the widths of the incoming arrows must be equal to the sum of the widths of the outgoing arrows.

©Bergey & Govin, Stimuli Eds, 2024 -

Historical and epistemological perspectives

In 1842, the German physician, Robert Mayer presented the value of the mechanical equivalent of heat. He started from the principle that “any cause equals to its effect”. How did he use this? By vigorously stirring water in a vessel, he observed that the only effect was that the temperature of the water increased. He then said that the agitation was the cause and the resulting heat was the effect. He postulated that “something” associated to mechanical action should be equal to “something” associated to the heat produced. He then introduced a new term. He called the cause “force” and the effect “force”. As he started from the idea that 'cause=effect', then 'force=force'. So he said that “force” does not vary. Since it does not vary, he said that the force is conserved. How could he argue that force is conserved, whereas the two observed phenomena are very different from each other (the mechanical action of stirring the water and the heat, as evidenced by the increase in the temperature of the water)?. In order to argue for this conservation, Mayer added the idea that the “force” is “transformed”. So one form of “force” (mechanical action) is transformed into another form (heat). These properties of Mayer's “force” - “force” is indestructible and transformable - have been adopted for energy. This can be seen in the principle of conservation of energy: energy is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

In 1843, Joule, a young man who performed experiments as a hobby, carried out an experiment to prove that heat is not a substance but a kind of motion. At this time indeed, heat was considered as something material associated with an object. When two objects interacted, the total quantity of heat couldn’t change. To prove that wrong, it was necessary to show that in some situations, this total quantity could vary. It is what he showed in his experiments, where the temperature increases with the mechanical action, then the total quantity of heat is not constant.

To prove this, it was only necessary to show that the “amount of heat” in a phenomenon can vary. Why so? If it can vary, it cannot be a substance. If it was not a substance, then according to the science of the time, it had to be motion. The experiments showed that the amount of heat varied, so heat should be a kind of motion. He asked whether there was a proportionality between the mechanical action used in the experiment and the heat produced. To answer this question, he carried out the same experiments and determined what we call the mechanical equivalent of heat. Between 1845 and 1850, he carried out experiments - the paddle wheel experiments - to determine the mechanical equivalent of heat more precisely.

In 1851, Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) introduced the term 'energy' into the theory of heat. The word existed in the lexicon and meant 'activity'. The meaning of energy changed over time. So it began to subsume the approaches of Mayer and Joule, as if they had both done the same thing. They agreed on the mechanical equivalent of heat; they differed on the interpretation of the phenomena. Mayer did not claim that heat is motion, but rather that it was “a form of (force) energy”. In the 1880s, different British scientists came up with the idea that energy was a “real thing that moves in space”, and from this time, we still have the idea that energy is transferred. The development of the concept continued and became confusing. The Nobel laureate Richard Feynman said in the 1960s: “It is important to realize that in physics today we have no knowledge of what energy is” (Feynman et al., 1963, Sect. 4–1). Nowadays, many physicists still make themselves this question: What energy exactly is?

For this reason, the conceptual approach proposed in this resource is not focused on the definition of energy, but on its operative use to describe, predict and explain natural phenomena around us in terms of energy transfer, energy conservation and energy degradation.

-

Suggestions of use

Prerequisites

As discussed in the previous section, there is no need for a formal definition of energy before engaging with the comic, since this definition is controversial and may lead into an abstract and meaningless statement. In contrast, students can use simple physical magnitudes such as temperature or motion to intuitively use the idea of energy, such as “the more temperature the more energy”, “the more velocity, the more energy”, etc. By using this reasoning intuitively, we assume that we will likely encounter misconceptions and confusions regarding energy throughout the learning process (see students point of view section, above). These misconceptions—such as energy being a tangible substance, the belief that energy is lost rather than transformed, or the misunderstanding of useful versus non-useful energy—will emerge as students engage with the comic and activities.

The role of the comic and the accompanying activities is to help students confront these misconceptions and progressively build a coherent model of energy based on key scientific ideas (see Conceptual Approach section above). By following the story and reflecting on energy-related situations, students are expected to move from intuitive but incorrect understandings to a structured and scientifically sound conceptualization of energy. The discussions and experiments will serve as scaffolding to guide this conceptual development.

Practical activities to promote discussion

One effective way to reinforce students’ understanding of energy conservation is through hands-on experiments that allow them to observe and analyze real-world energy transformations. A simple but insightful experiment involves dropping balls of different materials and sizes from the same height. By carefully observing and discussing the results, students will note that the energy of the falling ball is transferred to the sand and the environment, producing an increase of temperature and sound upon impact. This experiment serves as a concrete demonstration of equivalence of energy in different initial states: dropping a mass two times heavier is equivalent to dropping a mass two times higher.

Another engaging activity involves exploring historical attempts to understand perpetual motion machines. Students will analyze designs from different periods and identify why such machines ultimately fail. This discussion highlights the principles of energy dissipation and entropy, reinforcing the understanding that energy transformations always involve some loss to the surroundings, typically in the form of heat. By critically examining why perpetual motion is impossible, students develop a deeper appreciation for the laws of thermodynamics.

Modeling with visual representations

The use of Sankey diagrams helps visualizing energy transfers within different systems. Students can analyze various real-world energy scenarios, such as a car engine or a household heating system, and map out how energy flows through these processes. By distinguishing between useful energy and dissipated energy, students can reflect on efficiency and how optimizing energy use is a key concern in engineering and environmental science. This approach encourages them to think beyond theoretical concepts and consider how energy conservation applies to technological advancements and sustainability efforts.

©Bergey & Govin, Stimuli Eds, 2024 Linking to Socio-Scientific Issues (SSI)

To further contextualize energy discussions, students can explore contemporary socio-scientific issues related to energy production and consumption. One way to do this is by examining global energy consumption trends, analyzing real-world data on energy usage in different countries and economic sectors. This approach allows students to understand how energy demand has evolved over time and the challenges associated with balancing energy needs with sustainability.

A related discussion can focus on energy efficiency and how technological advancements help optimize energy use. By looking at case studies, such as energy-efficient appliances, electric vehicles, or improved insulation techniques, students can evaluate the practical applications of energy conservation. This encourages critical thinking about how science and engineering contribute to solving energy-related challenges.

Finally, students can engage in debates or projects discussing the environmental impact of different energy sources. By comparing renewable and non-renewable energy, they can weigh the benefits and drawbacks of various energy production methods. This discussion can lead to an exploration of the role of policy and innovation in shaping a sustainable future. By linking the concept of energy to real-world issues, students gain a broader perspective on its significance beyond the physics classroom, fostering a more interdisciplinary and applied understanding of the topic.

-

Complementary resources

To support and extend student learning, different complementary resources are available. You can download these activities in an editable document.

Document 1: Short Energy Concept Inventory

This short inventory consists of multiple-choice questions aimed at diagnosing students’ pre-existing ideas and potential misconceptions about energy. Covering topics such as gravitational potential energy, energy transfer, and conservation, this assessment tool helps educators identify areas that require further clarification and allows students to track their conceptual progress over time.

Document 2: Scientific Questions to answer after reading the comic

This resource contains a set of questions designed to be answered only after students have read the comic. The questions encourage students to reflect on key concepts such as energy conservation and transformations while drawing direct connections to the story. They also promote critical thinking, asking students to explain physical phenomena and represent energy flows through diagrams.

Document 3: Investigating how objects sink in sand

This hands-on activity explores the relationship between an object’s mass, drop height, and how deeply it sinks into sand. By experimenting with different variables, students can analyze the equivalence of different initial states in order to produce the same effect. The resource provides structured inquiry steps, predictions, and data analysis opportunities.

Document 4: Understanding energy dissipation through Sankey Diagram

The activity in Document 4 engages students in analyzing energy dissipation through the use of Sankey diagrams. By visualizing energy flows in different systems, students explore how energy is divided between useful energy and dissipated energy. This approach encourages them to critically assess efficiency and understand the principles of energy conservation. Through various exercises, they will modify and interpret Sankey diagrams to reflect different real-world scenarios, helping them grasp the impact of energy dissipation and the importance of optimizing energy use.

Document 5: Investigating perpetual motion machines

This resource challenges students to critically examine videos claiming to showcase perpetual motion machines. By analyzing mechanical interactions and identifying sources of external energy input, students engage in scientific reasoning to debunk the feasibility of perpetual motion. The activity emphasizes the second law of thermodynamics, highlighting why energy dissipation prevents machines from running indefinitely without an external energy source.

Document 6: Video of a supposed Gear-based Perpetual Motion Machine

This video showcases a mechanical system that claims to operate indefinitely without an external energy source. The mechanism consists of interconnected gears, levers, and rotating elements that appear to sustain motion on their own. However, by analyzing the forces at play, students can critically evaluate why perpetual motion is impossible under the laws of thermodynamics. The video serves as a tool for identifying hidden energy inputs, frictional losses, and energy dissipation within mechanical systems.

Document 7: Video of a supposed Water-Based Perpetual Motion System

This second video presents a water-driven system that seemingly continues moving without external energy input. The setup involves a continuous flow of liquid moving through pipes and wheels, suggesting an endless energy cycle. Students are encouraged to analyze the components, question the role of gravity, and identify why energy losses through friction and resistance make true perpetual motion unattainable. By deconstructing the claims made in the video, they develop a stronger understanding of energy conservation and dissipation.

-

Teaching sequence propositions

The following teaching sequence is designed to integrate the reading of the comic with structured activities that help students analyze and refine their understanding of energy concepts. The sequence spans two class sessions and includes discussions, hands-on activities, and assessments to consolidate learning.

First Class (1h)

Individual Questionnaire - Document 1 (20 min)

Students begin by answering an individual questionnaire designed to assess their prior knowledge and identify potential misconceptions related to energy. This diagnostic activity, provided in Document 1, allows students to engage with key concepts before being introduced to the comic. The teacher collects and reviews responses to tailor the following discussions.

Individual Reading (20 min)

Students then read the comic individually, allowing them to familiarize themselves with the storyline and scientific themes without prior explanation. They are encouraged to take notes on any confusing aspects or surprising insights they encounter while reading. The comic serves as a way to introduce energy concepts progressively, allowing students to engage naturally with the ideas.

Post-Reading Activities - Document 2 (20 min)

After reading, students complete structured activities based on Document 2, which contains guiding questions that prompt them to reflect on key concepts introduced in the comic. These activities are designed to provide a framework for discussion of some of the concepts included in the comic. Students work in small groups to compare their answers before engaging in a teacher-led class discussion.

Second Class (1h)

Experiment: Investigating how objects sink in sand - Document 3 (20 min)

Students participate in a hands-on experiment using Document 3, which focuses on how objects of different masses and drop heights sink into the sand. They conduct experiments by dropping different objects and measuring the depth they sink, recording their observations. The goal is to connect these experimental results to the concept of energy transfer, reinforcing how kinetic energy moves into other objects upon impact. The teacher facilitates a discussion to link the idea of equivalence of different states that produce the same change.

Sankey Diagram - Document 4 (20 min)

Students retrieve the Sankey diagram already presented in the comic, a visual representation of energy transfers in a system. Using Document 4, they analyze different examples and identify how energy flows through various processes. The focus is on distinguishing between useful and dissipated energy, reinforcing the concept of energy degradation and efficiency in real-world applications.

Analyzing Perpetual Motion Machines - Document 5, 6 and 7 (20 min)

Students watch and analyze videos of supposed perpetual motion machines. They use their understanding of energy conservation and degradation to critically evaluate why such machines cannot function indefinitely. Through this activity, they strengthen their grasp of the second law of thermodynamics and the impossibility of creating a system that runs without continuous energy input. Class discussion follows to deconstruct the mechanisms in the videos and reinforce why energy transfers always involve some loss to surrounding objects or systems.

Optional Extensions

For classes with more available time or for deeper engagement, additional activities can be incorporated:

Global Energy Discussion: Students examine data on world energy consumption and discuss the implications for sustainability.

Comparing Energy Transfers: Using real-world examples, students evaluate efficiency in different systems and how technology aims to optimize energy use.

Debate on Energy Use and Efficiency: Students engage in a structured debate on whether energy efficiency measures should be mandatory in industries and households

-

References

Bächtold, M., Munier, V., Guedj, M., Lerouge, A., & Ranquet, A. (2014). Quelle progression dans l’enseignement de l’énergie de l’école au lycée? Une analyse des programmes et des manuels. Recherches en Didactique des Sciences et des Technologies, 10. https://doi.org/10.4000/rdst.932

Bächtold, M., & Guedj, M. (2014). Quelle progression dans l’enseignement de l’énergie de l’école au lycée ? Recherches en Didactique des Sciences et des Technologies, 10, 63–94.

Bächtold, M. (2021). Introducing Joule’s paddle wheel experiment in the teaching of energy: Why and how? Foundations of Science, 26(4), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-020-09664-2

Coelho, R. L. (2024). On Joule's paddle wheel experiment in textbooks. Physics Education, 59(2). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1361-6552/ad2104

Lawrence, I. (2007). Teaching energy: Thoughts from the SPT11–14 project. Physics Education, 42(4), 402–406. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9120/42/4/011

Goldring, H., & Osborne, J. (1994). Students’ difficulties with energy and related concepts. Physics Education, 29, 26–31.

Credits

-

Script

Lau Bergey, Victor Lopez

-

Storyboard

Barbara Govin

-

Illustration

Barbara Govin et Aline Rollin

-

Webdesign

Gauthier Mesnil-Blanc

-

IT development

Clément Partiot

-

Translation

Margaret Rigaud

-

Science education research in physics

Agathe Chirier, Cécile de Hosson, Victor Lopez, Valentin Maron, Paulo Mauricio, Hayriye Ozkan, Lionel Pelissier

-

Production

Stimuli Eds

-

Licence of use

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

-

ISBN

978-2-9593956-5-9

-

Publication

Janvier 2025

-

Additional pictures

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Codex Atlanticus (Codex Atlanticus), Copyright Veneranda Ambrosiana Library