Ocean

Digital comics

Her Majesty the Ocean

Aboard an oceanographic ship, Iris records her travels in her journal. Her diary entries inspire the Supertroupers to write a play on rising water levels. But when a Pacific island is submerged by the ocean, their project becomes a plea for the oceans. They move back into the classroom, and invite other students to help them finish writing the play.

Share this link ith your students

-

Overview

In this episode, Soupertrouper member Iris has the unique honor of joining a research team on the high seas. Taking inspiration from this experience, the Soupertroupers create a theater play on the theme of ‘Oceans.’

The Science Comic explores the intricate relationship between climate change and the ocean ecosystem, highlighting how they influence one another. Its primary aim is to convey the complexity of this biological system while encouraging students to enhance their system-thinking skills. In recognition of current educational research that knowledge alone is not enough to promote environmentally friendly behaviour, the episode also seeks to engage students on an emotional level, fostering a personal connection to the ocean. The goal is to strike a balance between revealing alarming realities and inspiring proactive energy, motivating students to envision and work toward future solutions rather than feeling overwhelmed. Additionally, the Science Comic provides numerous opportunities to conduct follow-up research and design classroom experiments. -

Starting points: students' point of view

The aim of this episode is to help pupils understand the importance of the ocean, particularly in the context of climate change. By understanding the components and processes that take place in the oceans, students should be able to better understand the changes that are currently taking place. But the ocean is a complex system, i.e. a system made up of a number of heterogeneous elements that are characterised by a range of non-linear interactions and are subject to external influences at different scales (Lesne, 2009). Complex systems are also characterised by the existence of emergent properties, i.e. properties at the global scale that are qualitatively different from the interactions of the elements at the local scale from which these properties nevertheless arise (Jacobson & Wilensky, 2006).

To understand a complex system, we need to grasp the multi-level organisation, heterogeneous components and dynamic processes involved. This requires a change in the focus of our understanding: it is no longer just a question of identifying the elements that make up the system, but of understanding its structure, i.e. the interactions and associated mechanisms, its dynamics, i.e. how the system evolves over time, and its control (Kitano, 2002). It is not enough to know the properties and behaviors of isolated elements in order to understand the overall behaviors of the system. It is also necessary to study the complex and hierarchical relationships between the structure of a system (the what, the elements, the components of the system), the mechanisms (the how, the behaviors of the elements of the system) and the functions, i.e. the why of a system (Hmelo-Silver, Marathe, & Liu, 2007).

Several studies (Assaraf & Orion, 2005; Fournier, 2015; Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007) have shown that students have difficulty understanding complex systems:

- A focus on the structure of the system rather than the underlying processes.

- Identification of simple causalities but not of connections within the system, nor of complex causal relationships.

- We take little account of the temporality and spatialization of system processes.

- The search for central control rather than an understanding of multiple dynamic interactions.

More specifically, about the oceans and global warming, some students link rising sea levels with global warming, but they almost never mention the impact on marine life, the state of coral reefs or climatic phenomena (Delplancke & Chalak, 2024; Shepardson et al., 2009). Pupils have a simple conception of the oceans and the Earth's climate system and have difficulty conceptualizing them on global temporal or spatial scales.

-

Conceptional approach

The topic of oceans offers numerous points of connection across nearly all scientific disciplines. Depending on the perspective, different approaches can be taken that cover a wide range of scientific aspects. Accordingly, this episode is designed as a collection of thematic pathways that can serve as starting points depending on the lesson structure and preferences.

The episode itself highlights two key aspects:

- Firstly, the observations and concepts presented convey an impressive image of the ocean as a (living) system, which is also influenced by the human species. In relation to climate change, this ecosystem is a critical component from both a physical and biological perspective.

- Secondly, the science comic highlights the aesthetic and subjective dimensions of the topic. Various studies on environmentally friendly behavior show that knowledge alone is insufficient to promote environmentally conscious action. Equally important are the personal relationships and attitudes learners have toward the environment.

The term "ocean" evokes highly individual ideas and associations among learners, influenced in part by geographic differences. They feel connected to this ecosystem in different ways and to varying degrees. The episode provides an opportunity to make these prior conceptions explicit and to explore the affective aspects of the subject alongside the scientific concepts.

-

Historical and epistemological perspectives

The oceans cover around 71 percent of the Earth's surface and are a true mystery. Their exploration has evolved over centuries, and today we know that they are far more than just large bodies of water - they are habitats, climate regulators and sources of many of our natural resources. For students, the history of ocean exploration is exciting because it shows how humans have conquered the unknown, developed new technologies and expanded our understanding of the Earth.

The history of ocean exploration goes back a long way. Even in ancient times, people ventured into the ocean, but their knowledge was very limited at the time. The ancient Greeks and Romans drew the first maps and described the coastlines, but without a deeper understanding of the oceans themselves. They often regarded the sea as a dangerous and inaccessible element. In the Middle Ages, the idea of an ‘infinite ocean’ dominated, full of myths and legends. Ships mainly travelled along the coasts and long voyages across the open ocean were rare. It was only with the great voyages of discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries, such as those of Christopher Columbus or Vasco da Gama, that the western world gained new insights into the geographical dimensions of the oceans and discovered new trade routes. From the 18th century onwards, scientists began to systematically explore the ocean. The development of more accurate maps, improved navigational instruments, and the organisation of expeditions such as James Cook's made the oceans increasingly accessible. Of particular importance were Cook's three voyages in the Pacific (1768-1779), which helped to provide the first detailed overview of marine geography. In the 19th century, the first scientific oceanographies were produced, and with the invention of sonar and submersibles in the 20th century, the oceans could increasingly be explored in depth and with greater accuracy.

The oceans are not only geographical entities but also play a central role in the global climate. For a long time, they were regarded as an almost inexhaustible resource without recognising their importance for the climate and ecological balance. Today we know that the oceans regulate the global climate because they absorb CO2and store heat. In addition, their biodiversity is incredibly rich and many of the deep marine ecosystems have only been discovered in recent decades. With today's technologies such as satellite measurements, modern diving robots and deep-sea submarines, we are able to explore life in the deepest and most remote regions of the oceans. Despite these advances, however, the ocean remains a place of mystery. It is estimated that around 80 per cent of the ocean floor is still unexplored.

What is interesting and relevant for schoolchildren today about the oceans? First, exploring the deep oceans is an adventure that comes with many challenges and technologies. The idea that we have only explored a fraction of the oceans leaves room for countless discoveries. Daily reports about new species, mysterious deep-sea volcanoes or plankton species that influence the climate make the topic lively and topical. The importance of the oceans for climate change is another major topic. Sea levels are rising, coral reefs are dying, and many sea creatures are threatened with extinction. This makes it particularly relevant for pupils as they realise how our activities affect the oceans. Environmental protection and the sustainable use of the oceans are increasingly becoming key topics in the classroom, and marine research offers exciting prospects for environmental protection in the future.

In addition, the interdisciplinary approach of ocean research allows students to combine topics from geography, biology, chemistry and physics. They learn how different scientific disciplines work together to understand the complexity of the oceans. This is an excellent opportunity to experience the connection between theory and practice and to understand why ocean science plays a key role in global science. Exploring the oceans shows us that there is still much to discover - and that makes it an exciting and lively topic for students interested in the future of our planet.

-

Suggestions for the use of the Ocean episode in the classroom

Focus on Ocean as a Social Scientific Issue

Part I: Introduction into the topic Oceans (approxim. 15 minutes)

This topic is a great way to begin with an association exercise. Give your learners a moment to imagine the setting. You can help them get into the mood by playing ocean sounds (such as waves, seagulls, or the sound of the sea) using an audio device.

Possible Instructions for the Association Exercise:

To introduce the topic, I’d like to do a little imagination exercise. If you want, you can close your eyes.

With your eyes closed, imagine you are traveling slowly (across roads and fields) toward the sea. You can already smell the salty air, and the sound of the waves gets louder as you get closer. Now you see the beach. Imagine sitting in the sand and watching the waves. Take a moment and notice what thoughts come to mind. What do you see in your imagination? What do you hear? What do you feel?After the learners open their eyes, ask the learners to share their thoughts in a digital tool (e.g. Mentimeter) or moderation cards to create a word cloud with the ideas and words they came up with. Use the word cloud to talk about the learners' associations in a classroom conversation and/or to establish a starting point for the (scientific) elaboration of the topic of Ocean.

Part II: Lecture Session and In-depth Study of an Elective Topic (approxim. 40 minutes)

Prepare the students for reading the Science Comic by introducing the main characters and their background information: the teenagers Tom, Diane, Iris, and Titouan are members of the amateur theater group Soupertroupers. In connection with their plays and rehearsals, they encounter various scientific topics. In the current episode, they create a play about the ocean.

Following, the students read the Science Comic independently. Ask the students to stop the reception after the first two chapters. Before they move on to the third chapter, they can choose from two different topics. Let them work in pairs. Using the worksheets, they will either deepen their knowledge about coral bleaching or develop their ability to shift perspectives regarding political decisions on tourism in protected areas. Both optional tasks include informational texts, illustrations and so-called concept cartoons.

Learners Choice Task A): How does coral bleaching occur?

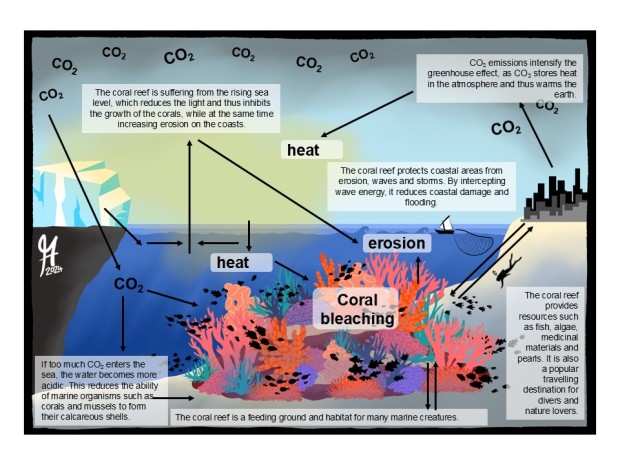

This topic focuses on the scientific phenomenon. You will explore the coral bleaching discussed in the Science Comic.Informational text: To describe complex relationships in biology, they are often viewed as biological systems. A biological system is a group of different components that interact with each other and their environment. Through these interactions, a change in one component of the system can affect other components or the system as a whole.The ocean can be considered a biological system. Coral reefs are an important part of the ocean because they provide habitats for many organisms and bind carbon dioxide in their calcium skeletons, helping to counteract ocean acidification. The death of corals due to coral bleaching has far-reaching effects on the ocean.Task 1: Reread the comic panels again that deal with coral bleaching to answer the following tasks.a) Describe to your learning partner what is shown in the comic excerpt.

Kapitel 2/Bild 26 - © Bergey & Govin, Stimuli Eds, 2024. b) A coral can also be defined as a system. Name the components that make up this system, as well as the term that defines their interaction.

c) Identify other components in the ocean system that interact with the corals. The following illustration might support your ideas.

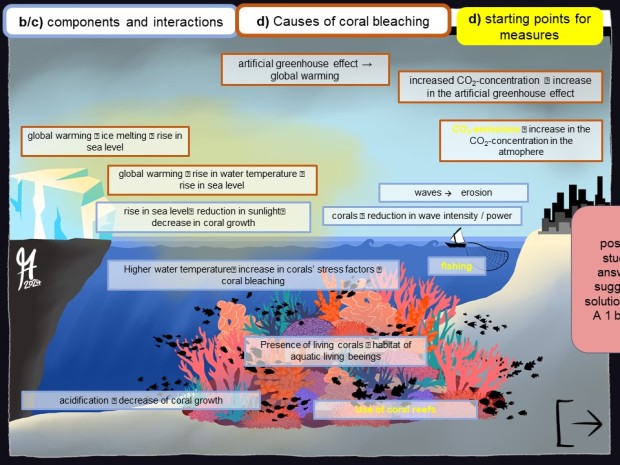

Ahnert, 2024 d) Discuss together which components and interactions cause coral bleaching. Name measures that could reduce or stop the bleaching of corals.

Possible students answers task 1b), 1c) and 1d)

(Ahnert, 2024) Task 2: Tourism at the Great Barrier Reef

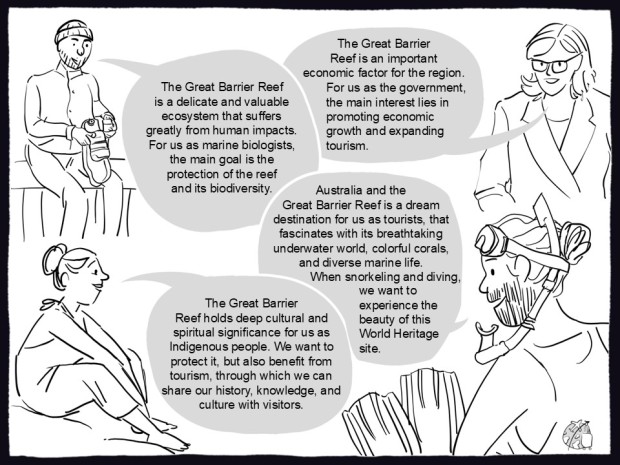

The Great Barrier Reef is the largest coral reef in the world and is located off the east coast of Australia. More than two million people from around the world visit it every year. The diverse fish species, whales, dolphins, and corals of the reef invite exploration through diving. However, there are also downsides that come with tourism. Different interest groups have varying opinions on whether tourism should be further expanded or restricted.

Look at the arguments in the speech bubbles in the Concept Cartoon. Discuss whether tourism at the Great Barrier Reef should be further expanded.

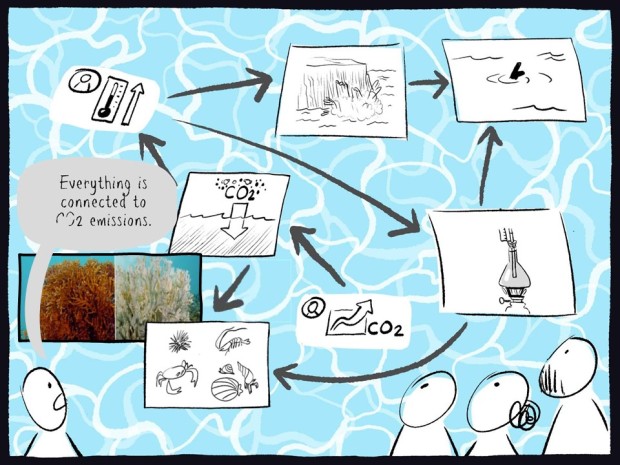

Platzhalter Bildquelle Task 3: Part of the innovative theater performance by the Soupertroupers is a so-called Concept Map. Look at the Concept Map. Imagine that CO₂ emissions worldwide are suddenly significantly reduced and answer the following questions:

a) Explain how the reduction of CO₂ emissions would affect the coral reefs. Would the bleaching process slow down or even stop? What could happen in the long term?

b) Complete the following sentence (there are multiple possibilities):

"If CO₂ emissions _______________, then __________________."

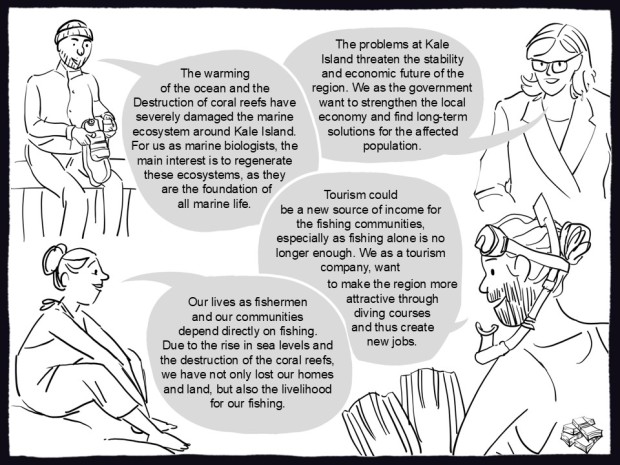

Learners Choice Task B): How fishing families think about the Great Barrier Reef

This topic focuses on the discussions people have around the use of the Great Barrier Reef. You will explore the different perspectives of the fishing families Iris met in the comic.

Task 1: The lives of the fishing families

Describe the living situation and the problems of the fishing families. The following questions may help guide you:

- What information do you get about the lives of the fishing families?

- What problems are they facing?

- How has their living situation changed compared to the past?

Task 2: Investment Program

a) Name different ways the money could be used. Collect arguments for and against each possibility. Use the information from the speech bubbles in the Concept Cartoon as well as your own ideas.

Platzhalter Bildquelle b) Discuss which of the possibilities is the most sensible.

c) Write a statement in which you describe how, in your opinion, the money should be invested to improve the situation of the fishing families.

Task 3: Part of the innovative theater performance by the Supertroupers is a so-called Concept Map. Look at the Concept Map. Imagine that CO₂ emissions worldwide are suddenly significantly reduced.

a) Explain how changes in the ocean would affect the problems of the fishing families. To what extent would their situation improve or worsen?

b) Complete the following sentence (there are multiple possibilities): "If CO₂ emissions _______________, then __________________.”

Part III: Conclusion - Potential Behaviour Influencing CO₂ Emissions (approx. 30 min.)

Using the previously discussed information, the lesson concludes with an exploration of action options to influence the CO₂ content in the atmosphere. Students brainstorm ideas for reducing CO₂ emissions and protecting the ocean. The “Think-Pair-Share” method can be used for this activity: first, students individually generate ideas, then discuss them with a partner, and finally share their ideas with the entire class. Digital tools like Oncoo can be helpful for this process, but an analog card query is also possible.

Ask the students to vote for their two favorite options. Different criteria can be applied: Which measure would they most likely implement themselves? Which would they recommend to friends or family members? Which do they consider particularly effective, and why? Further guiding questions can be: Which of the measures would you propose to representatives in the state or federal parliament? Which measure would you be willing to demonstrate for?

The responses can be discussed within the class.

Part IV: Word Cloud as Closure Session (approxim. 5 minutes)

Use the word cloud from the introduction to conclude the lesson. Engage in a brief discussion with the students in the plenary session, which can be supported by the following questions:

- What thoughts come to mind now after our lesson when you think of the ocean?

- Are your ideas from the beginning still relevant?

- Have you had new thoughts on the topic?

Focus on the ocean as a system (System Thinking)

Part I: Lecture Session and In-depth Study of an Elective Topic

Prepare the students for reading the Science Comic by introducing the main characters and their background information: the teenagers Tom, Diane, Iris, and Titouan are members of the amateur theater group Soupertroupers. In connection with their plays and rehearsals, they encounter various scientific topics. In the current episode, they create a play about the ocean.

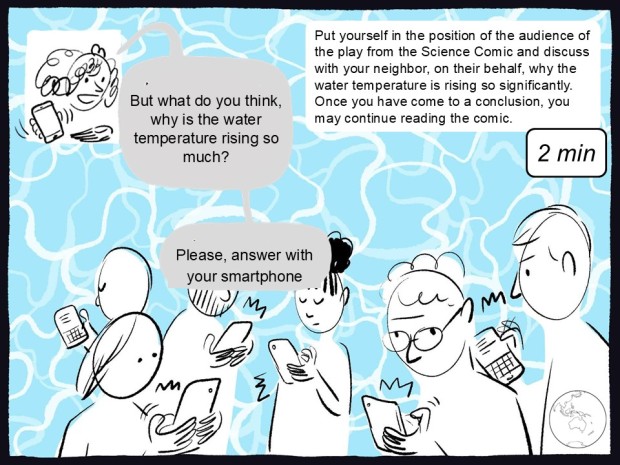

Following, the students read the Science Comic independently. Ask the students to stop the reception during the third chapter. The audience sets up hypothesis about the rising sea level. Encourage your students to adopt the perspective of the audience from the Science Comic in order to answer task 3. Afterwards, the students can continue their independent lecture.

Task 1: Put yourself in the position of the audience of the play from the Science Comic and discuss with your neighbor, on their behalf, why the water temperature is rising so significantly. Once you have come to a conclusion, you may continue reading the Science Comic.

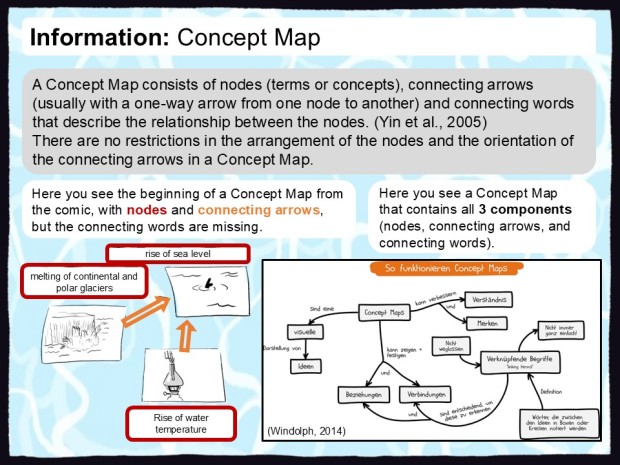

Part III: Concept Mapping (approx. 20 minutes)

For this task, share meta-information about the Concept Mapping strategy with your students. If wanted, provide the pre-structured Concept Map and meta-information about Concept Mapping as additional materials.

Platzhalter Bildquelle Task 2: Concept Mapping

a) Click through Chapter 3 of the Science Comic again and research aspects that could serve as nodes for the Concept Map. Write down your nodes on the lower half of the first worksheet.

b) Now, arrange your nodes on the second worksheet to create a Concept Map by linking them with arrows and adding connecting words.

c) Analyse your concept map with the following questions and make adjustments if necessary:

- Does everything still make sense to you?

- Are there any other connecting arrows that could be drawn or inserted as feedback loops?

- Should any nodes be explained more precisely?

- Should any connecting words be made more specific?

Part IV: System Thinking (approx. 20 minutes)

Using the presentation- see the complementary resources, have the students work out important characteristics and terminology relating to biological systems or present these in class. Then have the students work on tasks A (higher difficulty level) or B (lower difficulty level)

Advanced Level:

Informational text: Various components interacting with each other are the basis of a system. It can be differentiated from other systems and therefore has limits. The components themselves can as well be subsystems and can vary in their order and size. This is known as a hierarchy. Each system has inputs and outputs, which means that energy, substances and information can both enter and leave the system. If the inputs and outputs change over time, this is called system dynamics. These dynamics can be regulated via feedback loops, i.e. feedback between components and previous processes. (Gilissen et al., 2021)

Task 3 A-Level: Looking at your concept map, discuss with you partner which parts of your concept map can be classified according to which system characteristics (components, interactions, limitations, hierarchy, inputs and outputs, dynamics, feedback loops).

- Which of these characteristics do the nodes represent?

- Which of these characteristics do the connecting arrows and words represent?

Basic Level:

Informational text: Now you should look at the system components and system interactions. As you have probably already realised, nodes in your concept map often represent system components and the connecting arrows and words often represent system interactions.

Task 3 B-Level: Each of you selects a ‘’thread‘’ of nodes and connecting arrows on your concept map and, following the direction of the arrows, explains to each other the overall context contained in this thread. Use your concept map to discuss whether there are any key components. For example, it could mean that many other components are dependent on it. Select one of these key system components from your concept map and explain what part this component plays in the system.

Part V: Influence of the greenhouse effects on the ocean as a system

Share an input on the topic of the greenhouse effect. Depending on the students’ prior-knowledge of, this can be done as a teacher presentation or by repeating the facts with the students. The focus should be on the natural greenhouse effect, how it is amplified by CO2-emissions and the consequences it has on global warming. The students then use this information and the concept map to complete this task:

Task 4: Imagine CO₂ emissions were suddenly significantly reduced worldwide.

a) Use your concept map to explain possible changes to the system. Note which components and interactions would change.

b) Complete the following sentence orally (there are multiple possibilities): "If CO₂ emissions _______________, then __________________.”

Part VI: Solution of the Blackstory

At the end of the lesson, let the learners resolve the black story using the information from the science comic or unravel the story with the second card.

Créditos

© Texto: engl./dts. Moritz Ahnert, Laura Zöller, Nastja Hentschel, Julia Zdunek, Jörg Zabel, 2024

© Zeichnungen: Bergey & Govin, Stimuli Eds, 2024

-

Complementary resources

-

References

Literatura

Assaraf, O. B.-Z., & Orion, N. (2005). Development of system thinking skills in the context of earth system education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(5), 518-560. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20061

Chalak, H. (2012). Conditions didactiques et difficultés de construction de savoirs problématisés en sciences de la Terre : Étude de la mise en texte des savoirs et des pratiques enseignantes dans des séquences ordinaires et forcées concernant le magmatisme (collège et lycée). phdthesis. Université de Nantes ; - Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth. Repéré à https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00700798

Delplancke, M., & Chalak, H. (2024). Éduquer aux incertitudes climatiques : Comment l'étude des conceptions des élèves peut-elle guider l'action éducative ? Phronesis, 13(3), 50-64.

Fournier, T. (2015). Pensamiento sistémico y epistemología personal de adolescentes en clase de biología: Incidences sur la construction d'une représentation de la circulation sanguine comme système complexe. Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Marathe, S., & Liu, L. (2007). Los peces nadan, las rocas se sientan y los pulmones respiran : Expert: Novice Understanding of Complex Systems. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 16(3), 307-331.

Jacobson, M. J., & Wilensky, U. (2006). Complex Systems in Education : Scientific and Educational Importance and Implications for the Learning Sciences. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15(1), 11-34.

Kitano, H. (2002). Biología de sistemas : A Brief Overview. Science, 295(5560), 1662-1664. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1069492

Lesne, A. (2009). Biologie des systèmes-L'organisation multi échelle des systèmes vivants. Médecine/sciences,25(6‑7), 585‑587. https://doi.org/10.1051/medsci/2009256-7585

Mayer, V.J. (1995). Using the earth system for integrating the science curriculum. Science Education, 79, 375-391.

Shepardson, D. P., Niyogi, D., Choi, S. y Charusombat, U. (2009). Seventh grade students' conceptions of global warming and climate change. Environmental Education Research, 15(5), 549-570. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903114592

Credits

-

Script

Lau Bergey

-

Storyboard

Barbara Govin

-

Illustration

Barbara Govin and Aline Rollin

-

Webdesign

Gauthier Mesnil-Blanc

-

IT development

Clément Partiot

-

Translation

Margaret Rigaud

-

Scriptdoctor

Edith de Cornulier

-

Science education research in biology

Zofia Chylenska, Claudia Faria, Simon Klein, Maud Pelé, Joana Torres, Bianor Valente, Jörg Zabel, Julia Zdunek

-

Production

Stimuli Eds

-

Licence of use

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED

-

ISBN

978-2-9593956-6-6

-

Publication

January 2025

-

Additional pictures

Image 14: Illustration from the Report on the scientific results of the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-76 under the command of Captain George S. Nares ... and the late Captain Frank Tourle Thomson, R.N. Biodiversity Heritage Library, on line.